The Secret Life of Notebooks

Drafts, doubts, and the permission to begin

Emily Dickinson stitched hers by hand. Leonardo da Vinci’s were filled with flying machines and shopping lists. Ludwig Wittgenstein’s were written in fragments and questions. Even Marcus Aurelius jotted meditations to no one but himself. None of them wrote for the notebook, of course, but all of them wrote through it.

Like them, we turn to notebooks, not to be read, but to read ourselves. And that's where this first letter begins.

#Field Notes

Dear Writers,

Notebooks have always been a kind of private rehearsal — a place where lines are allowed to be strange, incomplete, or tenderly half-wrong. Though they rarely leave the desk, they contain whole worlds—unfinished, overheard, imagined. They are our escape, our vision, and our sounding board. Safe behind the covers or in an encrypted file, this is the place to work out ideas and flashings.

Sometimes, when we are lucky, language in the shape of poems accumulate there. And poetry being, I venture, the most personal of genres, those thoughts can be excruciatingly shy of the light.

“Private” is the key word. Perhaps your notebooks are hidden on a shelf deep in the closet or occupy a pseudonymed file on your laptop. Even if brazenly left in the open, have you given instruction to a trusted friend to destroy them when you’re gone?

I have.

The Secrets Within the Notebook

Notebooks have also been a place where words, lines, even entire compositions hide until the moment is right—if ever it is. There is judgment in revealing private writing. Personal and entirely too harsh. Where does this come from, this severe self-appraisal? And why, maybe even after years of publication success, does it persist?

“The worst enemy to creativity is self-doubt.” Sylvia Plath

These words come from Sylvia Plath’s The Unabridged Journals of Sylvia Plath, where she wrestles frequently and candidly with the effects of self-criticism, insecurity, and artistic paralysis. She explored the inner conflict between ambition and self-doubt deeply and often. Plath’s insecurities are well documented and reveal her recurrent thoughts on feeling estranged from her creative self.

We are our severest critics. And each critical blow cripples the inventive energy that yearns to escape.

Exiting the Fear, Entering the Flow

One might, in order to offset this fear, consider instead that what is written in the notebook (and by notebook, I mean anywhere rough drafts and inklings reside) is often processed in a state of suspended self-assessment. Free-wheeling intuition. A state of “flow”—that condition of mind that involves deep absorption and involvement, along with the loss of self-conscious grasping after.

Knowing this, one can feel more confident and more accepting. Tapping into the sub-conscious is crucial to letting go of the harmful critic. This mental state, identified as “flow” by Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi, combines deep immersion, full focus, and intrinsic reward.

“Flow is being completely involved in an activity for its own sake. The ego falls away. Time flies. Every action, movement, and thought follows inevitably from the previous one.”

Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi from Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience

There are ways to enter flow. The path in is personal, but the more often one enters the space, the more easily it is achieved. Consider the following:

Begin with a ritual

Light a candle, open the same notebook, make tea.

A simple act tells your brain, now we begin.Set a gentle goal

Not “write a masterpiece,” but “write for 25 minutes”

or “draft three lines.”Minimize discord

Eliminate digital noise. Use tools you love.

Clear your desk. Leave only what helps.Let go of outcome

Flow doesn’t care if what you make is good.

It only asks that you keep going.Start with what’s easy

Copy a line you love. Describe a scent.

Re-type yesterday’s paragraph. Let ease build momentum.Follow curiosity, not discipline

Flow is a partner, not a boss. Listen for the sentence

that wants to be written next.

Download this Entering Flow guide and tuck it beside your notebook for help escaping the insistence of full tilt reality.

For me, flow is akin to the roller coaster rides of my youth. In what felt like untethering from the earth, I was freed from the normal restraints of gravity and allowed perspectives that grounding prohibited. While in a state of flow, my thoughts can freefall and soar without restraint. Released from the power of inhibiting forces, the mind is generous and inspired.

The worst enemy to creativity may be self-doubt, but the notebook is its quiet antidote. Let it hold your wild lines, your unfinished truths. Let it silence the critic— not with perfection, but with presence.

“In the journal, I do not just express myself more openly than I could to any person, I create myself” Susan Sontag

#Frame & Phrase

Note: My prompts will always offer a layered approach. Use what you will or follow your own inspiration or instinct. Above all, allow yourself creative freedom.

“Beyond the Gaze”

What part of your internal child still watches the world from within?

This image invites a story, but don’t feel the need to tell it directly. Write your poem “sideways.” Speak through what’s left unsaid.

Begin with the eye

Start your poem with the gaze, yours, or someone else’s. Let it carry memory, suspicion, fear, or fierce love. Let the look do the talking.

Write from the inside of a held moment

This could be:

A memory of being comforted or shielded

A moment you weren’t sure you could trust

A time when someone tried to protect you from something they couldn’t explain

Use touch, scent, and texture to ground the poem in sensory detail.

Allow for contradiction

Let care and discomfort live together. This image holds tenderness, but also alertness. Let your poem inhabit that tension. What is said without being said.

Optional

Try shifting tone midway through, from guarded to open, or from observational to intimate. Let the poem breathe through more than one emotional register.

#From the Stacks

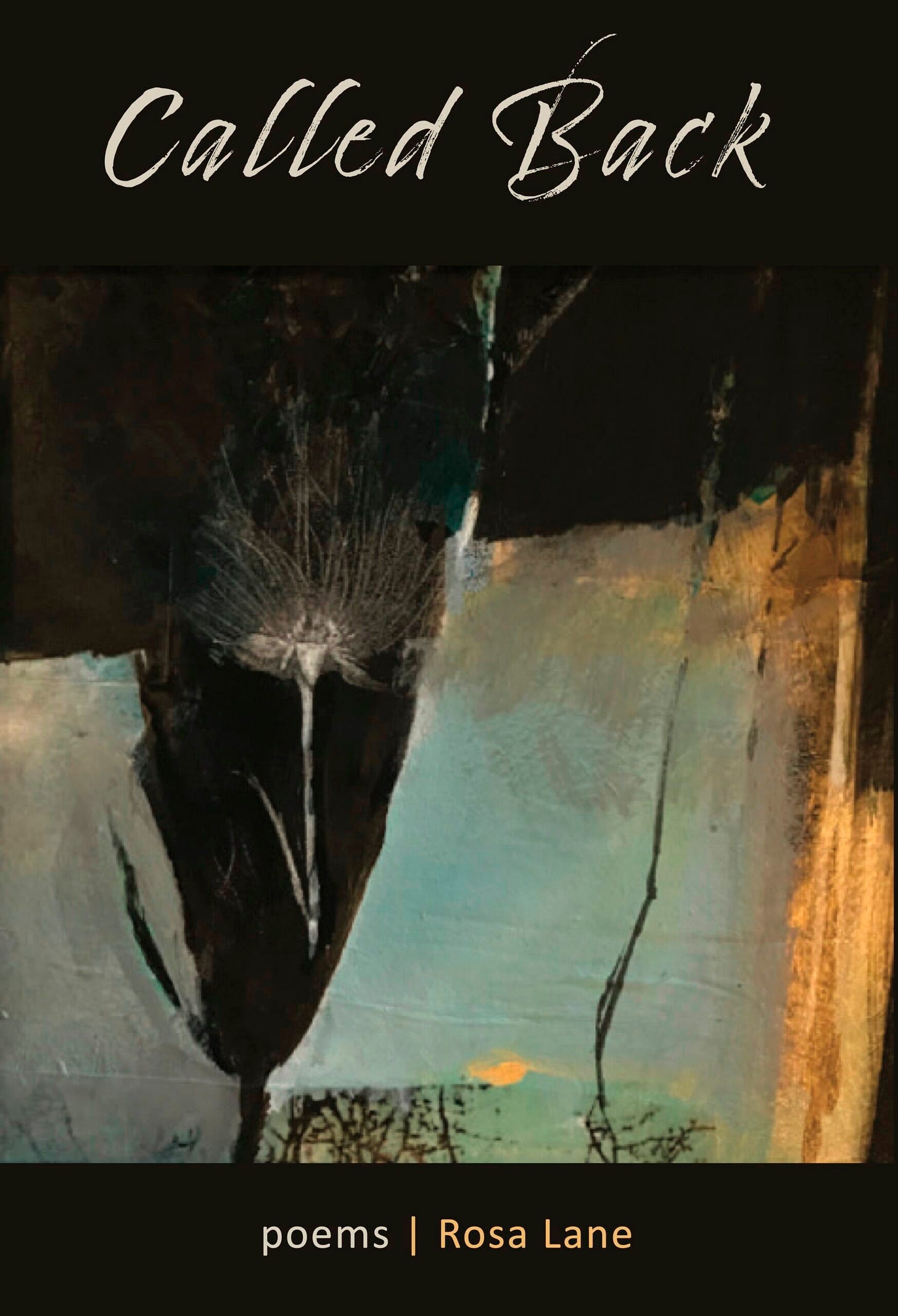

Called Back, by Rosa Lane, Tupelo PressDo pick up Rosa Lane’s book Called Back. Riffing off lines from Emily Dickinson’s poems, Lane writes a deeply intimate Dickinsonian dialogue. Her deep study of the poet’s work led to this lyrical exploration of Dickinson’s unordinary life—her sexual orientation, her estrangement from society, her well-hidden secrets amid the mores of a Calvinistic period. I find this book tantalizing. If you're interested in learning more about the book's content and themes, you will find this review insightful: Rosa Lane's Called Back, Reviewed by Frank Paino in Pedestal Magazine. Paino’s sensitive reading of the book is almost joy enough, but in reading it, you will, like I, feel the urge to delve into Lane’s groundbreaking poetry. This book is deeply intriguing, multi-dimensional, and one you will want to add to your library.

Here is one poem “Kiting April —” from the book, originally published in River Heron Review, Prize Issue, Spring 2023.

Reprinted with permission from Called Back (Tupelo Press, 2024).

Kiting April — A Pang is more conspicuous in the Spring In contrast with the things that sing Not Birds entirely — but Minds — Minute Effulgencies and Winds — —Emily Dickinson (1530, lines 1-4) find me in white — billowing south wind, flat chest shaped by darts. Inside my pocket, a poem folded on the back of an envelope teases my pencil. I push the breast-plow — garden thawed third week. Crocuses already blooming centuries ahead. I till and turn the bed, soak my seasonal brain like seed. Mud-kneed. I edge and furrow — winter forgiven. I reach for the jar, pour the whole garden into my apron- draped bowl. And where frost left its wound, I drop a seed into the o of pock — a soft vowel planted between consonants. Beware the clicking jaws of the aphid- mind. And how the emerald march of these tiny dots can skive a whole plot. And when sheaths crack open their specters, shoot up esophagi, unfurl their mouths for cupping copper blue, the poem will unfold its envelope, release every pinion, slant upward full timbre, skirr the empyrean.

Thank you for tagging along with 10 poetry notebooks’ first newsletter. I am honored by your presence.

I’ll be back each Thursday with prompts—and every other Thursday with quotes, notes, thoughts, and ramblings. The first few posts, including this one, are open to all subscribers. Starting with the fifth, a preview will be available, and the remainder of the newsletter will be available to paid subscribers only. Free subscribers will continue to receive a weekly prompt, Page & Pen, and an occasional newsletter, Ramblings.

I'd love to hear what you’ve written in your notebook lately. Feel free to share a thought, a fragment (what’s something from the previously unremembered past?), or simply say hello in the comments. Let’s keep community.

Write and thrive,

Robbin

Coming up in 10 poetry notebooks:

Thoughts on why we write the same poem (again), musings on the pen you choose, and always…thought provoking prompts.

Ooh saving this for later 🙏

Loved the whole post. So much goodness in it. Like this line: “Notebooks have always been a kind of private rehearsal — a place where lines are allowed to be strange, incomplete, or tenderly half-wrong.”