Poem as Map, Poem as Field Guide

Charting the interior landscape

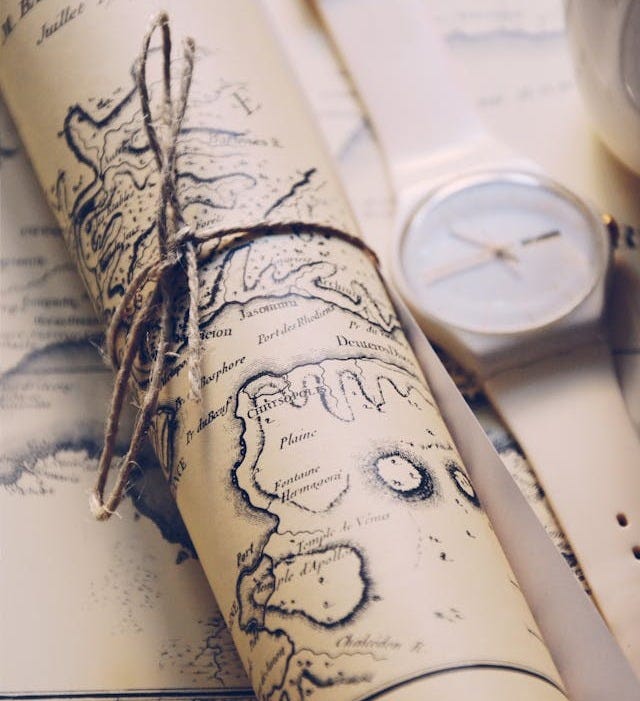

We don’t always know where a poem will take us—only that we must follow. Some poems are maps: charting interior landscapes, tracing memory’s fault lines, sketching the contours of longing or place. Others act as field guides, naming the wild things, offering clues, letting us see more clearly what’s already there.

This week’s column explores how poems help us navigate: not just the outer world, but the inner one, too.

#Field Notes

Dear Writers,

Let’s talk about where we’re headed when we write a poem.

Every poem begins with a kind of disorientation, the feeling that something must be found, even if we don’t yet know what is lost.

The impulse to write often arises before we understand what we’re writing toward. It’s a kind of listening-in-the-dark, a trusting fall into language. We write not because we have answers, but because something, a line, an image, a feeling, has stirred the silence, asking to be followed.

Poem as Map

Poems can function like maps, not just of place, but of experience, memory, emotion, and imagination. They chart terrain that is often invisible or internal, helping both poet and reader locate themselves in the landscape of being.

Writing into the void means letting go of the need for clarity, for control. It means walking without a map, and discovering, step by step, that the poem is the map — a map drawn only as we move, not a perfectly scaled rendering, but a record of terrain crossed, detours taken, silences survived.

Writing poetry is often an act of recalibrating: Where am I, emotionally? Where have I been? Where am I headed? Poems can chart the contours of grief, joy, trauma, longing, or love, treating these not as abstract states but as territories to traverse.

Think of the stanza as a topographical feature: an elevation, a depression, a clearing. Repetition might be a “return route,” while enjambment becomes a detour or rupture. When considered in the language of mapping, the structures of the poem become the map’s features whether topography or legend.

Just as maps represent the physical world, poems can sketch the psyche’s terrains, its uncertainties, discoveries, obsessions. Metaphors turn inward experience outward: a doubt might be a fork in the road; a memory, a cave. Syntax mimics movement: short lines can quicken the pace, while long sentences may feel like an endless path.

Additionally, certain poetic forms mirror the structure of journeys or maps themselves.

Villanelle: like a circular route you keep returning to, spiraling deeper.

Sonnet: contains a turn (volta), signaling a shift in direction, like a map’s key landmark.

Free verse: more exploratory, wandering without a guide but letting instinct lead.

Prose poems: unbounded blocks of thought: city grids, mazes, or satellite views.

Let your form reflect your poem’s journey. Does your poem need borders or openness? Is it a highway whose lines run to the horizon or a convoluted road with stops and turns?

Emotional terrain of Carolyn Forché’s work

I introduced a Forché poem in last week’s post. In “Lost Poem,” she reflects on a poem she once read and cannot find again. She writes, “The city itself is lost, and there is no road.” The elusive poem becomes metaphor for the fleeting nature of memory and speaks to the power of poetry to navigate the landscape of loss.

“The city itself is lost, and there is no road.”

Carolyn Forché

Forché’s choice of prose poem form becomes especially powerful because it mirrors the content: a fragmented, searching recollection, rendered without the interruptions of lineation. The poem becomes a kind of emotional cartography, a map drawn not with borders and roads, but with memory and loss. Its unbroken form mirrors the terrain of grief: continuous, nonlinear, and hard to navigate—yet guiding all the same.

Poem as Field Guide

Once we’ve found our bearings, the poem shifts. No longer just a path to follow, it becomes a way to notice—to catalog, to linger, to name the life all around us. After the journey comes the witnessing. The field guide teaches us to pause within it. A poem, too, can be a ledger of attention.

When poems function simultaneously as map and field guide, they chart the emotional or psychic territory a writer is moving through (map), while also pausing to examine the details of the world within that journey (field guide). A single poem can offer direction and description, path and presence, movement and observation.

Not yet a paid subscriber?

Join us for the rest of this issue including a side-by-side comparison of poetic approaches, an Ocean Vuong gem, a curated booklist, and this week’s multi-layered prompt. If you’re not yet a paid subscriber, now’s a great time to join us.